The code of this project is available at https://github.com/veglos/dotnet-auth-microservice

Table of contents

- A Clean Architecture

- The Hexagonal Architecture

- The Design

- The Auth Microservice

- The Project Structure

- Conclusion

1. A Clean Architecture

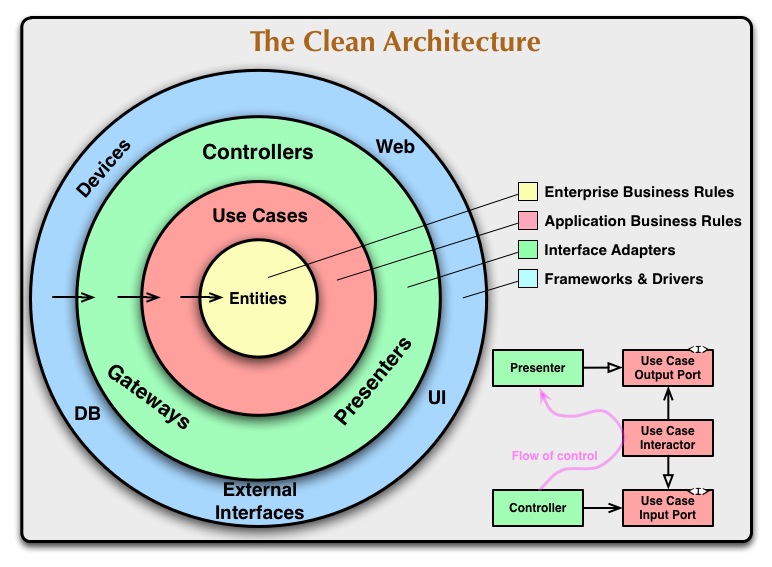

In 2012 Robert C. Martin published a blog article called The Clean Architecture where he wrote about the common features of different systems, like independence of the framework, independence of the database, independence of the UI, etc. Then in 2017 Martin published the book Clean Architecture that elaborate a further analysis on how a good architecture should be, but most importantly «why».

Figure 1.1: Robert C. Martin’s Clean Architecture Diagram

2. The Hexagonal Architecture

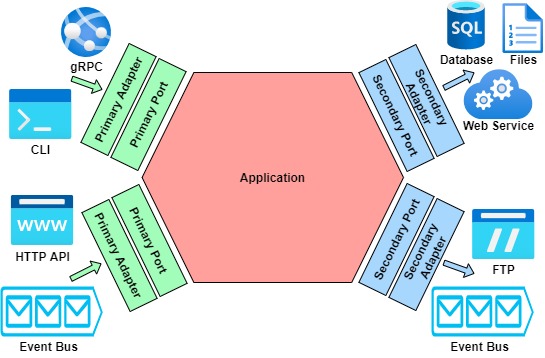

The Hexagonal Architecture was created by Alistair Cockburn in 2005. He has a complete explanation in his site.

Also known as the Ports & Adapters architecture pattern, it focuses on the Dependency Injection (DI) principle in order to

- delay the decision of what technology implementation to use, and

- change technology implementations later easily

This pattern relies mainly on four concepts: primary port, primary adapter, secondary port, and secondary adapter. They can be found with different names in literature. See table 2.1.

| Primary Port | Primary Adapter | Secondary Port | Secondary Adapter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incoming Port | Incoming Adapter | Outgoing Port | Outgoing Adapter |

| Driving Port | Driving Adapter | Driven Port | Driven Adapter |

| Input Port | Input Adapter | Output Port | Output Adapter |

Table 2.1: Different names for port and adapters according to different literature

Ports -both primary and secondary- are just the interfaces that declare what the implementation must do. Conversely, Adapters -both primary and secondary- are the respective implementations of the ports.

Primary represents a mean to «run» or «drive» the application. It could be a request to get/send data to/from the app or to start a background process. A primary port shows to the «outside world» how the application can be called. On the other hand, Secondary represents a mean for the application to interact with resources, like calling a web service or fetching data from a database.

In summary:

- Primary Port: Interface exposed by the application for it to be called.

- Primary Adapter: Implementation of the Primary Port to call the application.

- Secondary Port: Interface exposed by the application for external resources to be called.

- Secondary Adapter: Implementation of the Secondary Port to access resources.

I made the diagram shown in figure 2.1 to illustrate the difference.

Figure 2.1: Hexagonal Architecture diagram

3. The Design

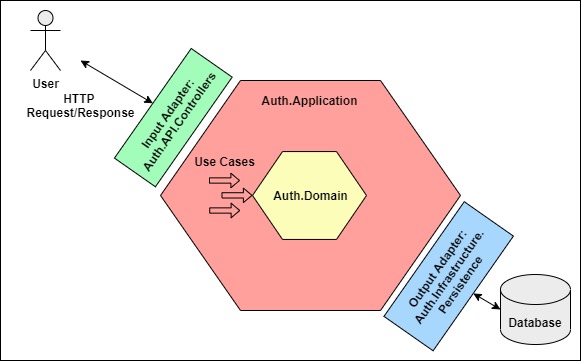

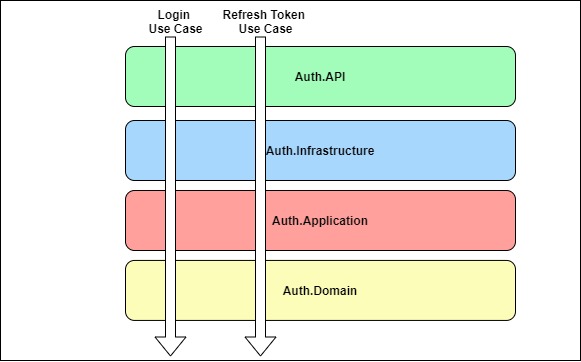

From the previous diagrams in figure 1.1 and figure 2.1, I designed the diagram displayed in figure 3.1. I kept the same color scheme to identify the boundaries.

Figure 3.1: Auth microservice architecture model

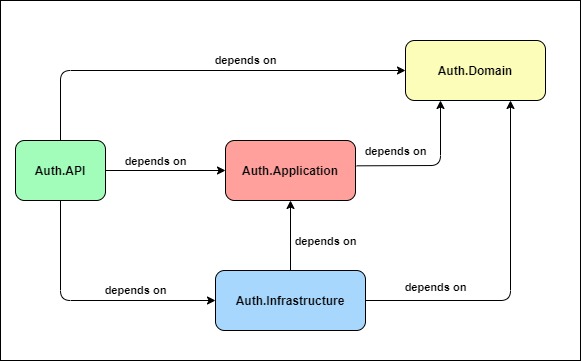

The solution is composed of four projects:

- Auth.Domain: Contains the enterprise business rules in classes (mostly POCO). It doesn’t have any dependencies except the .NET Framework itself.

- Auth.Application: Contains the application business rules, represented by the use cases. Depends only on the Auth.Domain.

- Auth.Infrastructure: Contains the specific implementation of services and repositories. Depends on the Auth.Application and Auth.Domain.

- Auth.API: Contains the controllers to be called by the user, and in turn, call the use cases. It also hosts the Microsoft Dependency Injection Container which explains why it depends not only on Auth.Domain and Auth.Application, but also Auth.Infrastructure *.

*note: It is possible to avoid the Auth.Infrastructure dependency by creating a DI Container project. I believe it’s not worth the inconvenience in this situation, but it’s totally possible.

Figure 3.2: Dependency relationship between projects

3.1. Use Cases

Use cases are the heart of the application, they execute the business rules. Here are some quotes from Uncle Bob:

Indeed, this is the first concern of the architect, and the first priority of the architecture. The architecture must support the use case

– Martin, R.C. (2017). In Chapter 16 Independence. Clean Architecture (p. 148). Prentice Hall.

The most important thing a good architecture can do to support behavior is to clarify and expose that behavior so that the intent of the system is visible at the architectural level

– Martin, R.C. (2017). In Chapter 16 Independence. Clean Architecture (p. 148). Prentice Hall.

[…], use cases are narrow vertical slices that cut through the horizontal layers of the system. Each use case uses some UI, […] business rules […], and some database functionality

– Martin, R.C. (2017). In Chapter 16 Independence. Clean Architecture (p. 152). Prentice Hall.

Figure 3.3: Use cases cutting through the horizontal layers

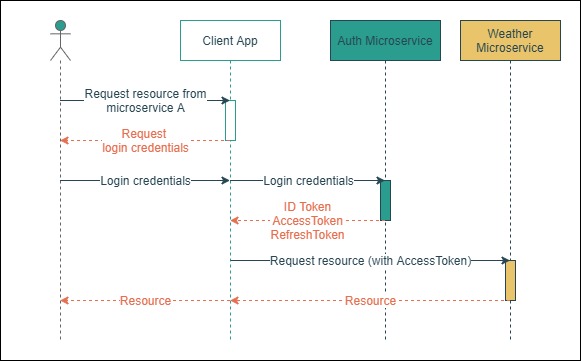

Our Auth microservice has two main use cases: Login use case and Refresh Token use case.

Given the login credentials, the Login use case returns an Access Token and a Refresh Token. The Access Token can be used by the client application to access other microservices that trust the Auth microservice. The Refresh Token is needed to get a new Access Token. More on this later.

4. The Auth Microservice

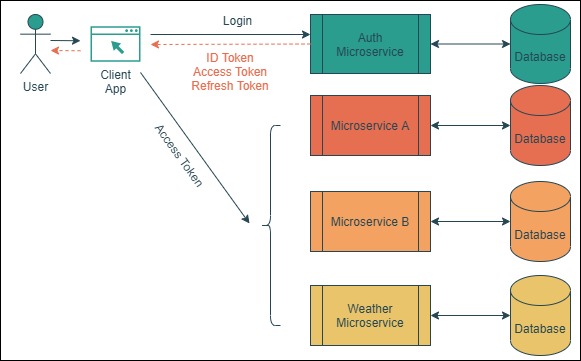

An Auth Microservice is a centralized authority that grants authentication and authorization (Auth for short) to a user to allow her/him access to a resource provided by other systems (i.e. other microservices) that trust said authority.

Nowadays it is imperative for most microservices to have authentication and authorization, and while it is possible to implement them in every microservice, it is far more convenient to rely on an Auth Microservice. We don’t want to login (ask for credentials) in every single microservice. Let the microservice focus on the scope they were meant to handle, nothing more.

Figure 4.1: The Auth Microservice handles the authentication and authorization of the user/client

4.1. What about an API Gateway?

The API Gateway may or may not handle authentication and authorization, and it can have more responsibilities than that, like response caching, circuit breaker, load balancing, etc., but it’s main purpose is to be a single entry point to the entire system.

4.2. OAuth 2.0, OpenID Connect, and Json Web Token

There are Id Tokens and Access Tokens. Id Tokens hold information about who the user is (claims), and the intended recipient is the client application (i.e. to show “Welcome Carlos!”, etc.). On the other hand, Access Tokens hold information about what can be done (scopes) in a resource (i.e. fetch the user’s photos, etc.), therefore the intended recipient of such token is the user’s resource. Figure 5.1 depicts how an Access Token works.

The Id Token is defined by the OpenID Connect Specification, whereas the Access Token is defined by the OAuth 2.0 Specification. The former must be sent in a JSON Web Token (JWT) format, the latter can be any string, including JWT.

It is not the scope of this article to deal with the Client App (or any front-end project for that matter), hence I dealt mostly with Access Tokens, not so much ID Tokens.

Figure 4.2: Sequence diagram of the process of authorization by Access Token

4.3. Access Token vs Refresh Token

There is a third and last type of token called the Refresh Token.

As previously mentioned, the Access Token allows the user to access a resource, however it has a short lifespan, and depending on the system, it could last between 5 minutes and 1 hour. This is important because if for some reason the Access Token get stolen, the attacker could only make use of it for a short time.

However, we don’t want to keep asking the user for her/his credentials in order ot get a new Access Token every 5 minutes. That’s why we issue a Refresh Token, which has a long lifespan, usually between 1 day and 1 week, and can be used by the client application to get a brand new Access Token without prompting the user with a login screen every time.

But could the Refresh Token also be stolen> Yes, but since a Refresh Token is assigned to a single user, it can be disabled and be forced to re-login again, preventing the attacker from getting a new Access Token.

Access Tokens cannot be disabled, unless we change the Private-Public key pairs, but that would disable every single token in circulation.

4.4. JWT, JWS, and JWE

Prabath Siriwardena does a wonderful explanation in his article JWT, JWS and JWE for Not So Dummies!. Basically, as the RFC 7519 says, JWT is a mean of representing claims (or scopes) between two parties, but the actual implementation occurs as a JSON Web Signature (JWS) or a JSON Web Encryption (JWE), or a combination of both. JWS encodes and signs the payload, whereas JWE encrypts the payload.

For this project I used JWT with JWS, and while it is possible to implement your own JWT library, it is highly recommended to use an already tested and popular library like the ones listed on https://jwt.io/libraries. I used the Microsoft’s System.IdentityModel.Tokens.Jwt library.

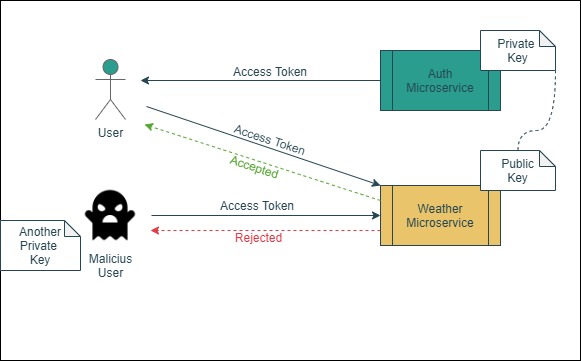

4.5. How do other microservices know the Access Token is legit?

There are two possible ways for a microservice to recognize that the Access Token received is actually from the Auth Microservice and not a malicious impostor (and/or that the payload has not been modified). The two ways are by a shared secret key or by a public-private key pair.

A shared secret key is used when the Auth Microservice uses symmetric cryptography to sign the payload. Another microservice would need to know the same secret key (hence a shared secret) in order to verify if the payload is true.

A public-private key pair is used when the Auth Microservice uses asymmetric cryptography to sign the payload, that is, it still requires a private key to sign it, but the verification can be done with just the public key, which as its name implies, it can be publicly distributed to the world without compromising the private key.

It is safer to keep the signing key (private key) in the Auth Microservice and only share the public key, no matter how much you trust the other microservices. That’s why this project uses asymmetric cryptography.

Figure 4.3: Simplified example of asymmetric cryptography

5. The Project Structure

As stated before, the solution is made of four projects.

5.1. Auth.Domain

1

2

3

4

Auth.Domain /

├─ User.cs

├─ RefreshToken.cs

├─ Claims.cs

The first and most important layer. It contains the enterprise business rules. It is quite simple because the RefreshToken class and the Claims class are part of the User class, so it could have been just a single .cs file.

The scope of the Auth Microservice is narrow. The domain classes are enough to encompass the authentication and authorization.

5.2. Auth.Application

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Auth.Application /

├─ Enums

├─ Exceptions

├─ Ports /

├─ Repositories

├─ Services

├─ UseCases

├─ CreateUser /

├─ Login /

├─ RefreshToken /

├─ SignOut /

├─ IUseCase.cs

├─ Request.cs

├─ Response.cs

Just as the plans for a house or a library scream about the use cases of those buildings, so should the architecture of a software application scream about the use cases of the application

– Martin, R.C. (2017). In Chapter 21 Screaming Architecture. Clean Architecture (p. 196). Prentice Hall.

Auth.Application holds the “screaming” part of the architecture that tells us what the system do. Just by looking at the UseCase folder, it is apparent what the application does: Create a user, Log in, refresh a token, and sign out.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Auth.Application /

├─ Ports /

├─ Repositories /

├─ IAuthRepository.cs

├─ Services /

├─ IAuthTokenService.cs

├─ ICryptographyService.cs

If we zoom in a little bit, the Ports folder declares the interfaces of the implementations that the use cases will need in order to be executed. That means all ports here are secondary/output ports.

5.3. Auth.Infrastructure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Auth.Infrastructure /

├─ Repositories /

├─ MongoDB /

├─ Scripts /

├─ AuthRepository.cs

├─ MongoDbSettings.cs

├─ Services /

├─ Cryptography

├─ CryptographyService.cs

├─ Jwt

├─ JwtService.cs

├─ JwtSettings.cs

This project contains the secondary adapters. Basically, every external infrastructure that is not fundamental for the behavior of the application, like third-party services or databases. For example, changing from SQL Server to PostgreSQL or MongoDB does not change the behavior of the application (asi in, the use cases).

5.4. Auth.API

1

2

3

4

5

6

Auth.API /

├─ Controllers /

├─ AuthController.cs

├─ Program.cs

├─ Startup.cs

├─ appsettings.json

This layer in particular has two roles.

First, it is an HTTP API primary adapter: It receives HTTP requests and converts them into request objects that the application can process.

Second, it is a Dependency Injection Container that knows how to instantiate and configure objects in runtime in order to be injected in the application when it requires it. This project uses the Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection library. It is common practice to do this in an ASP.NET Core Web API project, since most application will only have HTTP Requests as inputs, so it’s easier to do this right here rather than creating another project for the DI Container. This is the reason why the Auth.API project depends on the Auth.Infrastructure project *.

*note: If the DI Container where in another project, for instance and Auth.DIContainer project, then the Auth.API project wouldn’t need to depend on the Auth.Infrastrutcure project. It’s just a matter of convenience why I did it this way.

6. Conclusion

There’s no silver bullet. There are many ways to implement a clean architecture, and many more ways to keep improving it forever. The important thing here is to grasp and understand the concepts and know how to identify them.

We must have a clear-cut boundary between layers and the direction of dependencies. The implementation of new features immediately “smell weird” when the boundaries are not taken into consideration. For example, if the Auth.Application requires to import a third-party library to access an Excel document then there is a clear violation of the dependency rule (the application cannot depend on the infrastructure), and necessary measures are required to correct it.